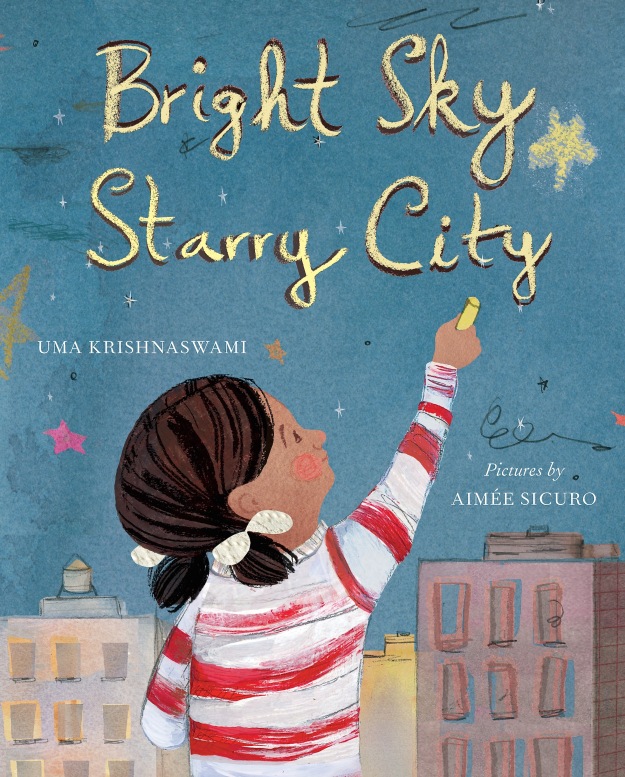

Bright Sky, Starry City © 2015 by Uma Krishnaswami, illustrations © 2015 by Aimée Sicuro. Reproduced with permission of Groundwood Books Limited (www.groundwoodbooks.com)

In “Bright Sky, Starry City,” author Uma Krishnaswami delivers both poetic children’s fiction and a textbook of sorts complete with a glossary, recommended readings, and an illustrated afterword that explains the solar system, planetary conjunctions, planetary rings, moons, telescopes, and light pollution.

In 2001, three scientists sounded an ominous warning about light pollution, writing that their research provided “a nearly global picture of how mankind is proceeding to envelop itself in a luminous fog.”

Pierantonio Cinzano, Fabio Falchi, and Chris Elvidge co-authored the journal article “The first World Atlas of the artificial night sky brightness” in which they calculated that two-thirds of the world’s population — more than 4 billion people — could no longer see dark, starry skies. And roughly 1.25 billion people had lost naked-eye visibility of the Milky Way.

The “loss of perception of the Universe where we live,” they wrote, “could have unintended impacts on the future of our society. … The night sky, which constitutes the panorama of the surrounding Universe, has always had a strong influence on human thought and culture, from philosophy to religion, from art to literature and science.”

Such poignant expression underscores the magnitude of what’s being lost as generations of children grow up having never seen the Milky Way or a sky brimming with stars.

Photo courtesy of Uma Krishnaswami

In “Bright Sky, Starry City,” author Uma Krishnaswami addresses avenues of accessibility, including a young girl’s path to dark night skies and the magnificent Milky Way.

But onto this nightscape of offending artificial light steps a young astronomer named Phoebe, the fictional star of the children’s book “Bright Sky, Starry City” in which author Uma Krishnaswami builds a narrative bridge strong enough to support the delicate relationships between heaven and Earth.

“Bright Sky, Starry City” (May 2015, Groundwood Books/House of Anansi Press) is, in simplest terms, the story of a girl’s love affair with the solar system. But at a deeper level, the story addresses avenues of accessibility: a daughter’s special relationship with her father; people’s ability to see the stars when the glare of urban light pollution is removed; and the strides that female scientists continue to make within the realm of male-dominated astronomy.

The story’s moral is this: The window to the universe is open to all, including a girl named Phoebe for one of Saturn’s moons.

The narrative begins with Phoebe helping her dad set up telescopes on the sidewalk outside his Night Sky store. In hopes of seeing Saturn and Mars together in the sky that night, Phoebe draws the solar system in chalk on the sidewalk, singing the planets’ names as she works: “Mercury, Venus, Earth, Mars, Jupiter, Saturn, Uranus, Neptune.”

Then comes an illustrative clue of connection. Beneath one small telescope, and next to a box of chalks, sits a stack of books. The book at the bottom of the stack bears an author’s name, BENDICK, with the capital letter “B” partially obscured and only a few letters of the book’s title showing.

Adding to this book’s mystery is its serendipitous path into Krishnaswami’s story. As Krishnaswami explained to me in a recent phone interview, she discovered the work of acclaimed author Jeanne Bendick while conducting research for “Bright Sky, Starry City.” Bendick, who died in 2014 at the age of 95, wrote and/or illustrated more than 100 children’s books with a primary focus on science and technology.

As a trailblazing woman in the science-writing world, Bendick championed futuristic concepts and presented complex ideas in ways that children could easily understand. “I was so surprised and so astonished that I hadn’t come across her work before,” Krishnaswami told me. “It was lovely. She was such a groundbreaker.”

But Krishnaswami did not mention Bendick in editing notes to her publisher. Nor did she tell first-time book illustrator Aimée Sicuro anything about Bendick’s books.

Amazingly, the appearance of Bendick’s “The First Book of Space Travel” in “Bright Sky, Starry City” is a coincidence. Sicuro discovered Bendick on her own, placing “The First Book of Space Travel” (originally published in 1953 and reprinted in 1960 and 1963) at the bottom of the illustrative literary stack.

Sicuro’s addition was “truly magical,” Krishnaswami said. “Somehow I had conveyed this notion about girls and stars, and it was absolutely the step I wanted her to go.”

Krishnaswami, who lives in Victoria, British Columbia, Canada, has written more than 20 highly acclaimed children’s books, including picture books, middle-grade novels, and retellings of classic tales and myths. But “Bright Sky, Starry City” is her first book about astronomy and how light pollution disconnects us from dark night skies.

The idea for the book came to Krishnaswami when she lived in a remote area of New Mexico about a three-hour drive from Albuquerque. In the late 1990s, night skies there were clear and dark, not threatened by a few lights from residential areas. But over the next few years, Krishnaswami watched the horizon go electric bright from an influx of commercial lighting.

Krishnaswami started thinking about what happens when the lights go out — when something dramatic happens, such as in January 1994 when an earthquake knocked out electrical power in the San Fernando Valley region of Los Angeles County, casting the region into darkness.

According to various newspaper reports, already terrified people were further frightened by what they witnessed in the California night sky. Emergency centers and the Griffith Observatory received calls from people describing a “giant, silvery cloud” — the Milky Way, our vast galaxy composed of billions of stars.

Krishnaswami weaves a similar narrative in “Bright Sky, Starry City” with one huge exception: In this fictional city, no one is afraid of the dark or the night sky when the lights go out during a thunderstorm.

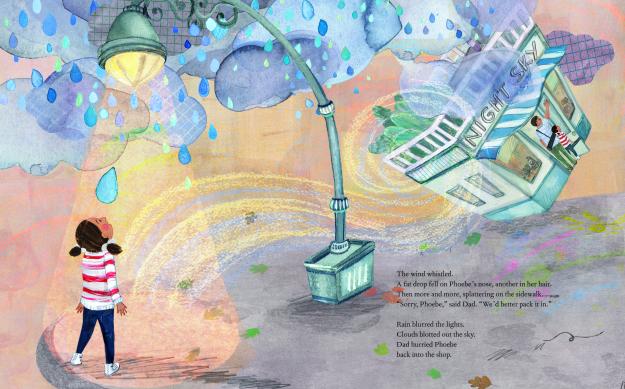

Bright Sky, Starry City © 2015 by Uma Krishnaswami, illustrations © 2015 by Aimée Sicuro. Reproduced with permission of Groundwood Books Limited (www.groundwoodbooks.com)

The plot takes shape as naturally as the Milky Way’s arc, set in motion by Krishnaswami’s poetic touch and Sicuro’s illustrations that retain the fluid softness of Phoebe’s sidewalk chalk drawings throughout the book.

As Phoebe draws, she worries she won’t be able to see Saturn and Mars up in the sky later that night. In a juxtaposed foreshadowing of what’s to come, the words of the first reference to urban light pollution are laid on a green-chalked section of Phoebe’s sidewalk solar system:

“Dad knew where to look, but city lights always turned the night sky gray and dull.”

Phoebe keeps drawing and dreaming, her childlike perspective illustrated by adults visible only from the chest down as they hurry past the kneeling girl whose high-top sneakers are adorned with Saturn and its rings.

The wind picks up as night falls. If they were in the country, Dad tells Phoebe, they could see Saturn and Mars in the western sky. Phoebe closes her eyes, Krishnaswami writes, wishing for all the city lights sending pale fingers up into the sky to disappear.

Bright Sky, Starry City © 2015 by Uma Krishnaswami, illustrations © 2015 by Aimée Sicuro. Reproduced with permission of Groundwood Books Limited (www.groundwoodbooks.com)

Phoebe’s wish comes true. Lightning cracks and thunder booms. Her chalk-drawn solar system is washed away by rain. And suddenly, there’s darkness. Electrical power is out.

Phoebe and her dad, who had taken shelter inside the store, go back outside. Above the newly washed city, Krishnaswami writes, Phoebe sees stars in the hundreds, some in constellations she knows only from pictures. And there, right where they should be, are Saturn and Mars close to each other in the western sky.

People crowd in the street outside the Night Sky store, talking, pointing, laughing, and looking, together under the stars.

Phoebe squints through a telescope, taking in Saturn’s rings and imagining the small, rocky moon for which she’s named. Then, she sees something new — a pale, gauzy, whitish band low in the eastern sky. “What’s that cloud?” Phoebe asks. “The Milky Way,” Dad replies. “That’s part of our galaxy you’re looking at.”

This excerpt from the story’s last page could stand alone as a night-sky poem:

“Phoebe breathed in the night, with all its stars and planets. … Soon the lights would come back on, and everyone would hurry off. But for a brief time, above the dark city, there was the bright night sky. The bright night sky, with the stars in their constellations and the planets wheeling in their orbits.”

Such elegant writing evokes Krishnaswami’s childhood. Born in New Dehli, India, she grew up as an only child whose closest companions were books.

Her father’s civil job for the Indian Army, which consisted of helping manage real estate and supplies for military installations called defense lands cantonments, required the family to move every four years.

In our phone conversation, Krishnaswami described herself as a loner, a girl who couldn’t count on having new friends in new places. So she turned to books, devouring a plethora of literary works, including A.A. Milne’s Winnie-the-Pooh adventures, Hans Christian Andersen’s fairy tales, and Beatrix Potter’s animal fables.

When her family lived on India’s West Coast, Krishnaswami hid away in the branches of a banyan tree, racing through the pages of English author Enid Blyton’s mysteries.

A young writer was in development: At the age of 13, Krishnaswami’s first poem was published in “Children’s World,” a magazine in India.

Now 59, Krishnaswami balances a busy writing life. She teaches in the low-residency MFA program Writing for Children and Young Adults at Vermont College of Fine Arts in Montpelier and is working on two new children’s books, including a middle-grade historical novel.

Krishnaswami has been writing her whole life. As a girl, she loved her father’s Remington Rand manual typewriter that he used for typing envelopes and she used as a toy, typing her name with the double black and red ribbon.

That relationship with words and machine continued during Krishnaswami’s early years as an author. As she tapped out stories on a computer, her young son Nikhil stood at her shoulder, yelling “Read it!” when she typed a period at the end of a sentence.

I asked Krishnaswami: Does Phoebe’s character resemble your childhood? Yes and no, Krishnaswami answered, explaining that while she wasn’t yet connected to the sky or the stars, she spent a lot of time in trees examining things close up. “Nothing could draw me away,” she said. “When I looked at something, I got super focused.”

Phoebe, as role model, displays that same focus as a budding scientist: a young and passionate astronomer showing other girls how they, too, can connect with the night sky.

Bright Sky, Starry City © 2015 by Uma Krishnaswami, illustrations © 2015 by Aimée Sicuro. Reproduced with permission of Groundwood Books Limited (http://groundwoodbooks.com)

Krishnaswami shares one other characteristic with Phoebe: As a girl, Krishnaswami also loved artful storytelling in the vein she learned from her mother, an instinctive narrator whose stories grew and morphed with each new telling. Krishnaswami told stories often to the adults who indulged her, and she staged plays for the kids in her neighborhood.

One of Krishnaswami’s earliest memories is of drawing on the wall with a green crayon, spinning a tale whose plot is long gone.

Fittingly, Phoebe appears on the cover of “Bright Sky, Starry City” where she has just drawn the book title in yellow chalk, a smudged star serving as the comma. The message is clear: The heavens are available for all, including a tenacious young girl whose vision of the universe comes into full, magical view.

Photo credit: Ethan Tweedie Photography

With the Milky Way clearly visible in a dark West Texas sky, a program leader points to constellations from the Frank N. Bash Visitors Center’s amphitheater at McDonald Observatory. Phoebe, the fictional star of the children’s book “Bright Sky, Starry City,” enjoys a similar view when city lights go out during a thunderstorm.